Friday, February 27

Ethical Administration of Nanotechnology

http://www.nanotech-now.com/papers/?area=reader&read=00003

Interesting paper by Chris Phoenix discussing the ethical implications of the commercialization of nanotechnology. In his paper, Phoenix discusses the ethical issues that arise from privately owned corporations making huge profits creating these new, rapidly growing technologies.

One point Phoenix made that I found quite interesting was the issue he raises regarding these companies having no ethical limitation or obligation to provide their discoveries and potentially life-saving technologies to those who cannot afford to pay for them. If these companies are the only ones with the capabilities of creating these technologies, it becomes even more of an ethical dilemma to provide those who cannot afford them with options to receive treatment.

Personally, I feel that there are huge gains that can be made by the use of nanotechnologies. With that being said, I strongly feel that there is an ethical obligation by the producers of these technologies to regulate what is produced and how it is produced, as well as the cost of the technologies and ethical implications regarding the technologies themselves.

Thursday, February 26

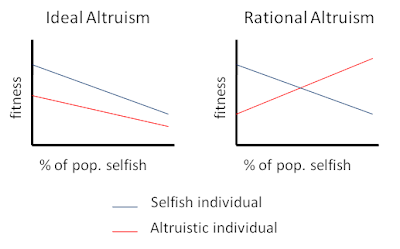

Given Matthew's affinity for graphs I thought I'd throw this up.

As we discussed on Tuesday one could postulate a selfish individual will always have higher fitness then an altruistic individual because they essential take advantage of the good nature of their counterparts (left panel).

If this assumption is correct and inheritability is assumed one would expect the percentage of the population to become more selfish over time. The model becomes unstable in the sense that one would expect no altruistic individual in the limit as time progressed.

Perhaps altruists are not ideal altruists but rational altruists. By this I mean they do not blindly self-sacrifice and help everyone, but try to distinguish between people trying to take advantage (scam) of them, and people who they can form reciprocal relationships with (you scratch my back, I'll scratch your back), or with whom they feel genuine empathy for. The resulting model would be stable over time, and would look like something on the right.

When the percentage of selfish individuals is small the selfish individuals can take advantage of the altruists because the rational altruists are less suspecting of malicious intent and the selfish have more opportunity. But when the percentage is high the rational altruists band together while the selfish must work alone.

Wednesday, February 25

Genetic Determination and Altruism vs. Selfish

In response to the question we asked in class yesterday: To what extent do Ruse and Wilson favor genetic determination?

I do agree to an extent that behavior can be affected by certain genes. For example it can be compared to those that have a history of diabetes. You are genetically pre-exposed to diabetes. However, I also believe that this definitely is not the only contributor to behavior. Obviously, an individual’s experiences and environment are also factors. This, I think, can be stronger than genetics. In the case of someone who is pre-exposed to diabetes, that person can choose to live a healthy lifestyle and greatly reduce their chances of having diabetes. The same is with the case of genetic determination on human behavior. Someone can go through certain experiences that change their behavior, or influenced strongly by another person. Genes control hereditary characteristics that serve as a foundation to our biological make-up, but the ability of an individual to reason, think, make decisions, and change their mind, I believe, in combination affect the behavior of a person’s behavior not solely genetics. I felt as though the argument made by R and W was strongly favoring of genetic determination of human behavior.

Also, we discussed in class the comparison between being selfish and being altruistic. This discussion made me conclude that perhaps they are intertwined together. Perhaps someone that is altruistic cannot be altruistic without, at the same time, being selfish to an extent. I would like to know what you think about this, but I will explain further what I’m getting at. I think that this can best be explained using examples. For example, when a monkey cries out when there is a predator, the monkey is being selfish to the extent that he wants HIS family to be warned to improve their survival chances. But one could say, what about a sterile worker bee? In the case that the bee goes out to defend the hive, you could say that he is definitely altruistic because he has nothing to gain, no offspring to protect, etc. However, the bee IS being selfish because he wants to insure the survival of HIS hive. Even though he doesn’t directly have offspring, he does have ‘family’. I hope these examples let you see what I’m trying to get at. I think that you have to be selfish to be altruistic, but to a different extent. What do you think?

Tuesday, February 24

The Biological Evolution of Morals

This would suggest, as Ruse and Wilson advocate, that moral norms are a product of the evolution of our biological nature, or in the very least that they are tightly connected. However, what about cultural norms that are contrary to our biology? There are two major examples that spring to mind: methods of population control and modern medicine.

Humans are unquestioningly biologically programmed to reproduce. However, given our problems with population, it is possible that many people have decided to forgo their natural urge to procreate in order to help curb overpopulation. An example of this being a cultural norm rather than simply an individual choice is China’s one child policy. Does this imply that because I feel the morally correct action is to not reproduce, I am actually acting immorally because it is contrary to my biological nature? Perhaps I have that moral inclination because I am biologically programmed to; in that case the only way that moral inclination could biologically evolve is if those who obtained it passed on to others in their genes, which is absurd.

Modern medicine is another great example. There is a prevalent cultural norm that saving the lives of others is a morally good action. However, it is also clear that many of the ailments modern medicine treats are a result of biology. For example, if I develop a deadly form of cancer because I had a specific gene that predisposed me to cancer, it is doubtless in my ‘biological makeup’ to die from it. Does that mean I shouldn’t seek treatment that could save my life? I’m not sure how this issue can be addressed from the stance that Ruse and Wilson take on morality and biology.

There are numerous other examples that are culturally normative and biologically opposed (i.e. ritual suicide), but I won’t delve into them here. My point is that if biological evolution and cultural change is so tightly related, as Ruse and Wilson claim they are, how do we account for the glaring anomalies? Any ideas?

(Works Cited: Ruse, Michael and Wilson, Edward. "Moral Philosophy as Applied Science". 1986: pg. 173-192)

Meeting 7 (3/3) — What Role do Values Play in Science?

Next time, we shall begin to consider the particular role that values play in science. A bit more background is in order. As I indicated at the end of our last class, the scientist-turned-historian/philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn was deeply influential in this regard. He noted on the first page of his epochal book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, that "History, if viewed as a repository for more than anecdote or chronology, could produce a decisive transformation in the image of science by which we are now possessed": and indeed it did. Rather that viewing science as a pristinely rational and disinterested pursuit (after something like the, perhaps charicatured, manner of Francis Bacon or Galileo), Kuhn offered a picture of "Normal Science" in which investigators simply took for granted much of the framework within which their investigations were carried out. Not everything was up for test. Good thing too, for if it were, chaos would probably result (you see this kind of chaos in the very early stages of scientific investigations where investigators are divided on the basic foundations of their field). Scientific revolutions are sudden changes in these "paradigms" of doing science which are not fully rational affairs. There's much more to say about this — at least a book's worth, it turns out —, but the crucial point for our purposes is that Kuhn turned the light of critical analysis on previously ignored social and value-laden aspects of scientific theorizing. Kuhn's investigations into the structure of scientific revolutions thus paralleled more general work conducted by some sociologists of science, in particular Merton (discussed in the Godfrey-Smith reading), who inquired into the norms of science and its reward structure in particular.

Much of this work is very interesting and enlightening. It's of course plainly true that science is conducted by people and people have all manner of normative, social, and political commitments. It's then natural to ask what influence these commitments might have on not just the general structure of scientific progress, but on the products of science. Here, the "Strong Program" in the sociology of science suggests that the image of science as a privileged form of inquiry is misguided. Science is instead "just another way of knowing" and perhaps relative to cultural values and norms. This salvo initiated what has been referred to as "The Science Wars", rumblings of which still echo. We won't be reading any sexy post-modern relativism, however (hilarious reading though it often is). Here's what's on tap for 3/3:

- Peter Godfrey-Smith, "The Challenge from Sociology of Science" (Chapter 8 of his Theory and Reality)

- Thomas Kuhn, "Objectivity, Value Judgment, and Theory Choice" (Chapter 13 of his The Essential Tension)

- Helen Longino, "Values and Objectivity" (Chapter 2 of her Science as Social Knowledge)

Origin of Morality

We all agree that we are taught fundamental moral issues(don't do this/that, this/that is bad etc) when we are a kid (and as we grow up) from parents, teachers, religion, basically from the environment. But how do we (or they, the people who taught us) know/realize that some moral stance are right while others are wrong ?

I think the first stage of moral development is the above but whether we believe them and hence apply them is determined by the agent/subject (individual). This is where I am hypothesizing that morality is linked with biology because whether we apply a moral stance or not is based on the biological outcome (real or realized/simulated). For example, a person A does not slap/club another person B (in a normal everyday scenario) because A knows that if he was at the receiving end himself he would feel physical pain, bruise/wound, tears etc… which are biological manifestations of the body. Though the example is simple minded (and hence could be more sophisticated), it tells us that the main incentive for taking a particular moral stance is biological mechanisms (both physiological and its psychological manifestations such as emotions etc). Therefore, though there may be some exceptions (individuals), in a random population of a particular society the majority would also base their moral standing on this biological incentive and hence these would form the moral ground/code of the society.

On conclusion, I think the first stage of moral development from environment provides a road map and selection of which road to take depends on biological incentives (just as given the choice most people take the asphalt road over the road with gravels, assuming both are of same distance not short-cuts, and you are not in a hurry ;-)).

Criticisms on Rawls Justice Theory

A critique of John Rawls Principle of Justice – Leonard Choptiany

A refutation of Rawls Theorem – Robert Paul Wolff

Rawls position on his principles was that they will be freely accepted by rational egoist in “contract situation”. But contract doctrines tread a narrow path between empirical fact and theoretical construction. For example, Fredrich Hayek’s “market as a free political mechanism” does not make clear how agreeing to egoist makes an institution just. Rawls reasoning for the contract doctrine is that, the principles account for strictness of justice because of the supposition that they arose from agreement among free and independent people.

Choptiany comments that neither equality nor the difference principles are sufficient as principles of justice because there is no specification of the size of allowed inequality for the difference principle. Apart from criticism of the principles, Choptiany criticizes the derivation of Rawls principles.

Rawls based his principle on the uncertainty of members of society on their role and hence each member would not propose a principle which is advantageous to themselves. However according to Wolff, if the members are rational (as proposed by Rawls) “equality of opportunity” principle would not necessarily be adopted because they would know their relative talents from others and hence the less able will opt for “random-selection principle” and the more able for “fair-competition principle”. Therefore, Rawls principle will be adopted based on probability which means that it no longer is a unanimous choice.

Wolff’s argument is weakened if these contractees did not know their distribution of talents as Rawls suggests. However, though there is uncertainty in contract situation the contractees know that the “veil of ignorance” will sooner or later be lifted and hence they would eventually know about the distribution. Therefore, the rational egoist will eventually adopt a new strategy to maximize his interest alone. This means that the contractees will have two strategies, an agreed strategy (like one of Rawls principle) for the contract situation and a 2nd strategy to secure egoists advantage. Even if each contractee knows about the eminent reversibility to 2nd strategy and hence maximize the security of all (maximin), the strategy in contract situation need not necessarily be carried out in practice because any post-contractual residual will be to the advantage of each egoist.

The maximin principle is analogous to Laplacean principle of insufficient reason which is a non-egoist commitment (moral stance). Thus Rawls rational egoists cannot implement maxmin principle without adhering to such moral stance.

Memes, genes, and queasiness over Wilson

This is a very reductionist and deterministic approach to genetics and our human dignity. We're assuming that everything about us as humans can be explained by genetic characters, and that if we possess certain genes we'll surely develop some particular trait or disposition. Ruse and Wilson seem to be taking the "nature" side only of the "nature vs. nurture" debate.

But what if it's not so simple (or complex, depending on how you ask the question)? Isn't it entirely possible that something outside of genetics has come to influence how we reason and brought us to where we are today? In pondering this question, the philosopher/cognitive scientist Daniel Dennett (Tufts University) came to mind (he gave a talk entitled "From Animal to Person" at WSU's Potter & Holland Lecture in September). One of his theories about the development of modern human consciousness and reason is that "memes" (a term coined by Richard Dawkins) have guided evolution of culture in a way analogous to how genes and viruses have guided our genetic evolution. Memes consist of things like cultural norms, language, even those catchy jingles that get stuck in your head, which influence the way we think and act. However, unlike materialistic genes and viral mutations, memes are passed on through their persistence in social structures and ideas. Thus, memes can be thought of as the "nurture" side of the debate.

For all we know memes and genes could be the same thing, but I'm more inclined to think they're not. I'd be willing to consider that they influence each other to a certain extent, but not that to which Wilson and Ruse are willing to concede. I think this is a very delicate issue with far-reaching consequences if we accept the notion that genes endow us with our moral reasoning capabilities.

Another point on this, which Kitcher addresses, is that Wilson and Ruse trap themselves in a very relativistic approach to morality. They argue that since different species have evolved down their own paths, they have different systems of exercising moral reasoning (if any at all). Aside from the fact that all members of the species Homo sapiens does not share the same moral system (which they acknowledge, but that's beside my point), my primary disgruntlement with this claim is that "species" have not evolved independently of one another. Our evolutionary histories are inextricably connected, at least to the extent that all of the organisms here today are here together and have been since some point in time. This would seem to diminish the idea that we have completely different systems of reasoning just because we have different genomes.

Maybe I'm beating a dead horse here; sociobiology/social Darwinism aren't taken all that seriously anymore in mainstream philosophy/science. I just think we need to carefully analyze what's being proposed here, because these arguments carry huge risks to the world at large.

There's plenty of room for expansion on this topic.

Monday, February 23

Additional Global Justice Readings

Values in Science

Peer Review Symposium

From: ISPR/KGCM 2009 [mailto:ispr@mail.ICTconfer.org]

Subject: Invitation to a Symposium on Peer Reviewing

Only 8% members of the Scientific Research Society agreed that "peer review works well as it is". (Chubin and Hackett, 1990; p.192).

"A recent U.S. Supreme Court decision and an analysis of the peer review system substantiate complaints about this fundamental aspect of scientific research." (Horrobin, 2001)

Horrobin concludes that peer review "is a non-validated charade whose processes generate results little better than does chance." (Horrobin, 2001). This has been statistically proven and reported by an increasing number of

journal editors.

"Peer Review is one of the sacred pillars of the scientific edifice" (Goodstein, 2000), it is a necessary condition in quality assurance for Scientific/Engineering publications, and "Peer Review is central to the organization of modern science...why not apply scientific [and engineering] methods to the peer review process" (Horrobin, 2001).

This is the purpose of the International Symposium on Peer Reviewing: ISPR (http://www.ICTconfer.org/ispr) being organized in the context of The 3rd International Conference on Knowledge Generation, Communication and Management: KGCM 2009 (http://www.ICTconfer.org/kgcm), which will be held on July 10-13, 2009, in Orlando, Florida, USA.

Sunday, February 22

Group Presentations

The Presentations

Group presentations are difficult things to pull off well. How do you integrate the contributions of each group member? There are a few different ways I might suggest. The simplest would be to simply offer separate presentations on different aspects of a topic in sequence. Say, each of the four people in the group give individual 10-minute presentations. This can backfire if the group doesn’t spend much time discussing their different presentations: they might end up being too disconnected or too overlapping (hearing the same basic stuff for the third time is a real drag for the audience). Another approach might be to design a single presentation (e.g., a slideshow), but share responsibility for its presentation. This is more work-intensive, but will tend to result in a more cohesive and effective final product. A group might also think about ways of diversifying the mode of presentation. A constant stream of powerpoint presentations can get boring and monotonous. Play to different group members’ strengths. Is someone a dynamic speaker and can present without slides? Could some of the group members engage in a debate? Could audience participation be used judiciously? Note that this can often be difficult: what happens when you ask a question and the audience just sits there (welcome to my world!)? I’m happy to entertain more creative ideas: showing short clips of films to illustrate an issue or prime the discussion, integrating music, theater, puppets, whatever. Just keep in mind that your grade will be based on not just entertainment value, but the depth, interest, informativeness, and argumentative effectiveness of the finished product. I will not allow presentations to run longer than one hour (groups that attempt to go over will simply be cut off), so use your time wisely and practice your presentation at least once so that you can be reasonably sure that you’ll be able to pull it off in the time allotted.

I will evaluate these presentations according to a rubric to be posted on this blog soon. There will likely be rows for the evaluation of the particular contribution (overall and in the presentation) of each group member. In all but exceptional cases, the collective will share in the individual successes and failures of the individuals — as it is in real life. Thus, it is your own best interest to help everyone in your group succeed!

Individual Work, Final Essays, &c.

Your final essay should be closely related to your contribution to your group. You will be conducting independent research on an aspect of your group’s topic which should inform the presentation. This essay (and certainly the research for it) should be well underway by the time of your presentation. But you may also think of the presentation as providing you an opportunity to get feedback on the main lines of your argument from me and the rest of the class. Final essays should come in at around 2,400-4,000 words and involve at least five scholarly peer-reviewed sources (other non-scholarly sources may also be judiciously used). They should have an philosophical/argumentative orientation: that is, they should not merely review some factual findings, but should instead attempt to establish an interesting and focused thesis. This might, of course, involve presenting those facts — but you should make the argument your focus. These essays are due by Tuesday, May 5th in class unless you are in the final group, in which case they are due by Tuesday May 12th in my office by 3:30PM. Late essays will be penalized by 5% per partial day late. I will produce a rubric for these final essays shortly, but it will closely resemble the rubric for the first essay (with the addition of a row for evaluation of the depth and appropriateness of your research).

Selecting Groups & Topics

Each group will have a fairly discrete topic. These can be wider or narrower, as the group decides. But I wouldn’t try to go too broad. It would be easy to fit five people under the umbrella of, say, “scientific responsibility”, but this might not give much direction to the class discussion. Ideally, you want a cohesive topic which still allows for distinct, non-overlapping contributions from four-five group members.

I’m fine with groups deciding to present on topics that we’ve already covered in class. There’s certainly more to be said about all of those topics. Other topics I contemplated addressing when I set out to design this course were: hot topics in bioethics (stem cell research, xenotransplantation, genetically modified foods/crops, &c.), the social structure of science (e.g., big governmental science, private science, big pharma, the allocation of scientific funding and resources), climate change and environmental sustainability, and so on. On this last note, as I’ve indicated before, since several people at the INPC will be speaking on the ethical issues surrounding global climate change, I would like one group to work on this general topic and to present on April 28th, the meeting preceding the INPC. Hopefully there are at least four people interested in tackling this topic.

I have created a discussion forum in Blackboard open to all. You may use this to propose topic ideas for others to think about (if you’re feeling generous), offer yourself up to work on certain projects or topic areas, advertise your areas of expertise or skill (do you have a science background? philosophy? economics? are you an experienced presenter? &c.). As I anticipate the best presentations to be largely interdisciplinary in character, it might well behoove you to attempt to form your group with diversity of skill sets in mind. My hope is that there will be enough diversity of topic preferences that groups will form quickly without my assistance. When this occurs — when you have a group of 4-5 people, please have a representative email me the composition of the group along with your proposed general topic. We need exactly four groups, two with five members and two with four members. If groups do not come together in this way by midnight on Monday, March 2nd, I will begin to take a more direct hand in their formation during the following class. Note that I might need to move people out of a group of five and or into a group of four in order to balance things out.

Group deliverables & progress

Once your groups are formed, I will create a discussion forum in blackboard for your group’s use to communicate with each other. You don’t have to use this — if email, phone, in-person meetings work better for you, by all means use them — but you may find it convenient to have some of your exchanges in a threaded discussion format in one place.

Your group should get together soon after its formation to talk about what direction you want to go in, how to divide up the work, what research assignments to use, and so on. I want to have an early-on meeting with each group, at least four weeks before your presentation to talk about what you’re intending to do, what your research is initially turning up, and ideally what reading assignments you’re thinking about making, and so on. The last part can wait if you want, but we’ll absolutely need to have a reading assignment for the rest of the class before the meeting preceding your presentation. Depending on what you decide to do, you might want to assign a chapter from the Rollin book as reading for the class. We can also scan articles or book chapters into PDF format to post online. I also have a number of books with essays in bioethics, environmental ethics, social studies of science, and so on. If you’d like to browse these in the philosophy conference room and scan something to take a more careful look at later, you’re welcome to give me a call in my office to see if I’m in and you can stop by (I’m reluctant to lend books, I’m afraid).

We’ll have at least one more meeting at least one week before your presentation in which we will discuss in some detail what you are intending to do, what your conclusions are, what your research looks like, and so on. Before this meeting, you should email me a single document composed by the group that will outline your main arguments (including each separate presentation), the different components to these presentations, and what research you have been conducting (including a reference list). This document will be graded and will account for a quarter of your presentation grade. I am perfectly happy to meet with you more than these two required times: just get in touch. The best times to request meetings with me tend to be Monday and Thursdays (mornings or early afternoons before 3:30) and during my open office hours on Fridays between 1:30 and 3:30. If none of those sorts of times work for all of your group members (it won’t do to just send representatives), let me know some times that would and we can work something out.

First Essay Rubric

Remember: these are due by 4/6 (sooner than you think!). I'm happy to talk with you about your first essays. See my first post about the essays.

Tuesday, February 17

Meeting 6 (2/24) — from Science to Values?

- Ruse and Wilson, "Moral Philosophy as Applied Science"

- Kitcher, "Four Ways of 'Biologicizing' Ethics"

Later, around the time Darwin published the Origin, shrewd thinkers in England like Malthus and Spencer were thinking hard about social problems like crime and poverty. Malthus, you might recall, was instrumental in Darwin’s thinking when he pointed out that a struggle for existence was inevitable so long as (unchecked) populations grew at a geometrical rate and resources linearly. This suggested to the so-called Social Darwinists that such social measures as the poor laws in England were doomed to fail. Criminals, the insane, the handicapped, the poor, and others were lumped into the “unfit” and Darwinian evolution supposedly tells us not to intervene in their removal from society. It is simply natural that they would be culled. They should be culled.

This line of thought, however, commits a number of mistakes. For one, it presumes that social undesirables form a homogenous class of evolutionarily unfit. For two, and more germane for our purposes, Social Darwinism commits what G.E. Moore called the naturalistic fallacy: the mistake of inferring what ought to be the case from what is the case. Just because something is “natural” (and this epithet would seem to need quite a bit of explanation), does not mean that it ought to be the case. So as we turn to the efforts of Ruse and Wilson to “biologicize” ethics, we should perhaps wonder whether they glide too easily from purported biological facts to moral principles. (Wilson, you might know, is the founding figure of the now mostly defunct movement of "Sociobiology"; he is still a prominent public biologist.)

What exactly is their project? This is essentially Kitcher’s question in his response. He identifies four different possible projects that Ruse and Wilson could be engaged in, concluding that none of them succeed in quite the way intended. This leaves open the question, though, of whether there isn’t some other way of "biologicizing" ethics. Is this a project worth doing? Does it have any hope of success? What might answers to these questions tell us about the relation between science and ethics?

Research Ethics

One of the good points that this article brought up was should there only be one “medical

ethic” in a country or should we all observe different ethics when it comes to research because different countries will have different beliefs/strategies. The author states, "Research ethics committees are, at least by tradition, embedded into a national framework, which itself is influenced by religion, history, tradition and the system of legislation of that country." So because different committees will have different views, does that mean we will never reach a full consensus of what is right and wrong in research?

Solomon Benatar Article

Monday, February 16

Issues in the Science World

Moral Monkeys?

These psychological studies, while fascinating, are always problematic for me. They tend to use inference to the best explanation as their sole rationale for concluding scientific results. Though this is often how science is practiced, it does beg the question, “Could there be another cause of these results?” Or as Justin asked his the previous blog, “Maybe this is a case of monkey ethics and not monkey morality?” Clearly though the monkey does what’s right which suggests morality, but we know that primates socialize in groups, so perhaps this is simply a case of herd instinct. It would seem that these researchers might be inclined to say there is a gene or collection of genes that evolved to form our conscience. I wouldn't necessarily reject this idea, but the criminal example at the end of the article seems to fall short of offering quality empirical evidence to support this claim.

Knowing such information also raises questions about the use of primates in scientific testing. If these animals potentially carry a higher level of awareness should we be performing harmful or fatal experiments on them?

Reaction to "When Man & Machine Merge"

When I was reading this I thought that this seemed really farfetched. Do you really think that human cloning will ever be allowed in the world, or even in the US? If it is, what kind of implication and new ethics will it bring the scientific community? The article also made me wonder if humans are supposed to live forever. I am not questioning it from a religious stand point, but from a population control standpoint. How many humans can this plant sustainably hold and if we live for hundreds of years, how many people could come to occupy this plant? I encourage all of you to read this article and look forward to hearing what everyone thinks about the implications of this technology.

Sunday, February 15

Knowing Vs. Doing

So, what is the true issue here? Is it that researchers don’t know what it ethical, or that they aren’t doing what is ethical? If scientists really don’t know the right thing to do, then requiring ethical courses for science majors may solve the problem. But, if we as a science community know the good and still don’t do it, then no amount of education is going to solve this problem. I do grant that ethical training would be valuable to better understand how to apply ethical principles in tough situation which have many facets. But, if we believe that more education will solve the problem, we are deceiving ourselves. The real question is how do we take the ethics we understand in our head, bring them down to our heart and then live them out in our lives. It is a change of character not a change of understanding which must take place in our universities, research centers and hospital.

Redesigning Science

After Tuesday’s discussion and thinking the Webster article it is rather clear that the current model for conducting, funding, and disseminating scientific research is far from perfect.

I think part of the problem stems from the necessity of quantifying the merit of researchers (for promotion, salary, etc.) and quantifying the merit of individual projects (for funding, publishing, validity, etc.). Because the current system uses publication numbers as a metric we have many “crap publications.” In truth, there are probably many different skills we are interested in measuring which aren’t really captured by the metric such as: meticulousness, creativity, work ethic, analytical ability, writing ability, logic, and so forth. So what might we do to change this system?

For arguments sake let us pretend we can ignore political issues and some of the funding issues and redesign the whole system using existing information technology. I envision online collaborative communities of researchers roughly divided by scientific domain. A typical researcher might belong to several different such communities. Each community would have guidelines dictating acceptable social behavior, and individuals not willing to comply could be asked to leave similar to how web forums are moderated.

Within each community individual projects would go through series of phases (the number of which would depend partly on the field of study and the standards set by the community). Examples phases might be design, implementation, analysis, write-up. During each phase a researcher could use the collaborative knowledge and experience of the community to work through problems and share successes with the community. Because everything is transparent collaborators get credit for helping researchers at competing universities or research labs. And because along every step of the way each project is being continuously critiqued and improved the science at the end is better. If people have differing ideas on how the project should go forward the project could be split and both ideas could be pursued similar to how open source software projects often split. If the project makes it through all the phases the final write-up is archived.

Credit would be divided between all individuals who actively contributed to the project providing more resolution into the actual contribution and capability of the individual researchers. Research money could go to the communities and the communities could decide how to use it as a group. Because of the collaborative nature they would focus on maximizing the utility of the money instead of just giving it to more prestiges institutions or based on nepotism.

Some elements are already taking place with scientific blogs, societies, and online publishing. The idea is to expand upon the positive elements of those trends, and create a system which fosters collaborative research and social transparency.

Saturday, February 14

Reminder: Darwin Week

Friday, February 13

Science Funding Difficulties

Thursday, February 12

First Essays

I do want to approve your topic before you get too far in — e.g., to make sure you don't try biting off more than you can chew (the biggest problem with short essays like this). Feel free to catch me before, after, or during class, in my open office hours (Fridays 1:30-3:30), or make an appointment to come see me some other time.

A good reason to start writing early is that I will grade and comment on your paper and give you the option to revise it for a better grade should you choose. Obviously, I can't do this for everyone in the final week before the deadline, though: your best bet is to get me a paper early when I don't have a big stack of them and I'll be able to turn it around in a few days. These first papers do not need to have a lot of research behind them (though they may): what I'm looking for is careful argument for a specific, focused thesis (between 1,800-2,400 words).

There's some advice about writing such essays on my website with some especially helpful links to others' sites at the bottom of the page. The best advice I can give you is: (1) Take your time and go through multiple drafts; and (2) Strive for clarity and simplicity above all. Rhetorical flourish rarely (in my opinion) outclasses simple, straightforward prose. Please follow this Formatting Guide when it comes to laying out your paper, handling quotes, references, &c. Notice the details. These count. I will post the rubric I will use to evaluate these essays shortly (need to extract it from Blackboard).

Wednesday, February 11

Response to Research Ethics Chapter

On page 211 of the Research ethics chapter, Webster discusses how their is a close relationship between the culture of research and the culture of money within these organizations. This raises the ethical dilemma of when announcements about scientific research and findings are made public and released to money markets. One serious dilemma here is are the executives in the biotechnology companies pushing their scientists to make big breakthroughs with their technology in order for the companies stock to increase? Also, are these companies giving bonuses and other financial incentives for their scientists to make these breakthroughs? This brings up the other dilemma of 'are these significant breakthroughs researched properly and truly accurate'?

Personally, I feel that their is a major conflict of interest present in these biotechnology companies. The financial gains that are associated with these companies based on breakthroughs made by scientists are significant. Since they are private sector companies, it is more difficult it is difficult to regulate the announcements of major breakthroughs in their research, so I feel that it is a very difficult issue to deal with. If these scientists do act unethically and give false information of their research, their could be very significant financial implications for the company, as well as the pure unethical nature of proclaiming a breakthrough in a certain science that could ultimately change peoples lives.

Post Labels

Global Health Research

There's more info on global health research here.

Tuesday, February 10

Look Ahead

Meeting 5: Health and Global Justice (2/17)

In meetings 6-8, we'll switch gears a bit to consider the relationship between science and values quite generally. This will involve doing a bit of philosophy of science. Meeting 6 (2/24) will address attempts to understand values scientifically via "sociobiology". Meeting 7 (3/3) will examine recent challenges that science cannot properly be thought of as providing us with "objective" truths due to its thorough contamination with values. In Meeting 8 (3/10), we'll read Part I of Kitcher's book which attempts to find a middle ground conception of science which places values and norms in their proper place.

The next two meetings (3/24 and 3/31) (during which we'll finish Science, Truth, and Democracy) will pick up the themes that we broach in Meeting 5: how should we, as a democratic society, go about ordering our scientific priorities. I'd like to have all of your first papers turned in by the Monday (4/6) after that Meeting 10. (I'll write more about those papers in a separate post shortly — running out of steam here). Then we'll have a week off (well, you'll have a week off: I'll be at a conference) — no class on Tuesday 4/7. [Whew!]

Our last four meetings (the 17th, 21st, 27th of April and May 5th) will be up to you. Mostly: As the 12th Annual Inland Northwest Philosophy Conference will take place from May 1st-3rd at UI and WSU on the topic "The Environment" and several of the papers (including the Keynote) will concern ethical and evidential issues surrounding global climate change, I'd very much like to see one group tackle that issue on the 28th so it's all in our heads before the conference (which you'll be encouraged to attend, btw). I'll send out a post in a few days with more details about how I'd like this to work, but you should be thinking now about different topics you'd like to work on in the context of a final paper/group project. Thumb through the rest of the Rollin book as for some suggestions. Or if any interesting ideas have occurred to you that you don't think are on others' radar, feel free to post them in the comments section here.

Meeting 5 (2/17) — Justice and Health

In many ways, I think the central problems in research ethics we've seen (and the non-obviousness of any compelling solutions to them) show up again in our next topic: research prioritization and health care justice. It seems that we can ask after the moral properties both of individual agents (researchers, doctors, politicians, citizens, consumers, &c.) and the social social institutions that they (we) collectively compose and utilize. It seems possible that our institutions through no particular dereliction of individual obligations can harm others (or encourage or allow individual harms). In the case of our academic institutions, these harms may be minor (still, we should take care to distinguish, even if vaguely, between regrettable features of a social institution — say, its discouraging people from being friendly — and harms that fall more clearly into the moral realm). But it is far from clear what any solution might look like. Is it more ethics training (as Dave and Dave suggest), greater transparency, more anonymity, standing juries, &c.? Or it may be that this is "as good as it gets": though problematic in this or that way, the institution is, all things considered, optimal.

In a similar vein, we can ask whether the institutions of scientific research are optimally pursuing research projects that they ought to pursue. Take disease research: it features a so-called "90/10 gap": "90% of humanity's burden of disease receives only 10% of the world's health research resources" (Flory and Kitcher 2004, 40). What should we do about that?

So far, you'll notice, we've tackled problems in science ethics that seem (generally) aptly characterized as "negative". Under what conditions is it permissible to utilize animals (including humans) in research? What should you not do as a researcher? It seems to me that the most pressing moral issues in science (and correspondingly, the most difficult) are those which ask whether we have any (positive) duties to adjust our scientific institutions to world need. I can't help feel that we do, but I'm still stuck on what that change should look like.

I'm assigning three articles that I hope will help guide our thinking:

- Benatar, "Justice and Medical Research"

- Pogge, "Responsibilities for Poverty-Related Ill Health"

- Flory and Kitcher, "Global Health and the Scientific Research Agenda"

As you'll see, we're starting to bump up against some difficult theoretical issues in ethics and political philosophy. John Rawls is a key figure in discussions about justice. I'll have something to say about the key features of his theory of justice, but if you would like to get a very good overview, head over the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. I take this meeting to be pivotal for our later discussion: Kitcher's book Science, Truth, and Democracy proposes a way to address questions about how we prioritize our scientific projects.

My response to today's class

When he was talking about getting grants, I was immediately reminded of something that happened over the summer. My lab group and another lab group in the Department of Chemistry applied for the same grant. It was a university-based grant available to any student in the department. Both proposals were, for what I believe to be, perfectly good areas to pursue. Our two labs are by no means in competition when it comes to our research—we’re physical chemistry and they are synthesis chemistry. Both labs are in two entirely different fields of work. Keep in mind that this is a grant that students apply for, not professors. The professor for the lab that got the grant introduced himself to one of the grant committee members before they met to discuss the grant. Needless to say, there were some upset people. The sad thing is our two fields of work complement each other as we both work RNA. This event burnt any bridges before they were even built. There could have been a lot of progress made with our two groups working together.

I would like to know if that professor thought he was being immoral or not. This seems out of place because his students love and respect him. Finally, this brings me to the actual point of my post. I fully endorse requiring an ethics course for science students. Future scientists should be aware of ethics and how it pertains to science. From a philosophy standpoint, the only way to address the problem is to have discussion. Letting people know there is a problem is sometimes enough to start change. Of course there will still be immoral people but with any luck they will slowly be dissolved into the “ether” of science.

On a side-point: the idea of peer-review reminds me of a quote by Winston Churchill: “Democracy is the worst form of government. But all others have been tried.”

Response to Proposal L

1) There is a possibility of the subject receiving a placebo.

2) Those who are given the placebo will have no risks associated with taking that placebo.

This information discloses all of the relevant information that directly relates to the subjects.

The other issue that our group had with this proposal was about the “risks” that were told to the subjects. Yes, we agreed that the knowledge of a potential risk during a pregnancy (which is already a stressful experience for the mother) could increase the stress levels of the participants. Even though the women would be giving their consent to participate in the study, there could be complications that arise after the subject has started participating in the study. If the effects of this placebo could have a psychologically beneficial outcome, couldn’t the thought of the risks have a reversed psychological effect on the subject? The mind is a powerful thing, and we can get ourselves to believe something if we really put our minds to it. Since we thought that this was such an important aspect of the study, maybe the researchers could put some psychological testing into the pre-screening to ensure that the women are prepared to deal with the associated “risks”.

There was one other aspect of this study I want to address… Since I am concerned with the lack of information given to the subjects, I am wondering why this wouldn’t apply to the controls as well? They are told that they have a genetic marker that makes them ineligible for the study, when in fact the researchers of this study are using the data collected form those individuals as the control data. It might be a little tricky to tell the women that they are actually controls for a study that has no medication administered, so maybe that is why they are told about the genetic marker (I am not sure how a medical researcher would approach this situation). But it seems that if we want to inform the participants as much as possible, we should be concerned that the control subjects are informed as much as the participating subjects.

Interesting Blog

Doctor who claimed MMR vaccine-Autism link may have falsified data

This is a perfect example of misconduct in reseach since we're talking about research ethics this week. See the article here. If you're interested, there's a ScienceBlogs thread discussing the issue here.

Monday, February 9

Proposal L and Animal Research

This leads me to animal research... I am a pre vet major, I have been an animal lover since I was a little girl, my life revolves around horses and other animals. As much as I love animals, I value the life of a complete stranger over any of my pets. Humans are superior, we have souls, emotions, intelligence, reason, etc. An animal has instincts and treats us the same way it would treat the alpha animal in its herd, pack, flock, or whatever. Animal research does not just benefit humans, it benefits other animals as well. So one cannot argue that humans are the only ones benefitting from animal research. We do have vaccinations, pain medicine, antibiotics, and cosmetics for animals. So when ten animals have to go through pain or discomfort, they are saving thousands and thousands more animals and humans from that same pain and discomfort. Honestly, I would give my dog or my horses to research if there was a chance that by doing so researchers could find a cure for my brothers disability. I dont think consent is the issue, an animal cant sign a consent. They dont even think that way! I have watched animals beat the shit out of another animal, chew their own legs off, eat their own young, and kill one another. So to compare babies to animals is ridiculous! Sorry to put it so harshly, but we dont eat our own young... I think that alone puts us above animals. With all the benefits that animal research has brought us, even if animals have to suffer, I think it is worth it to make advancements in science. If you dont think so, then again, stop taking cold medicine the next time you have a cold or dont take pain killers the next time you hurt your self, or use neosporin on your cut, or eat half the foods you eat, dont get the flu vaccination, if you get rabies or a snake bite dont go to the hospital for help, if or when you have children dont give your children cough syrup when they are horribly sick. Basically stop using any modern convience that you have in your house, because whether or not they are still testing those products on animals, they did have to test an animal at one point in history for that product to gain the knowledge whether or not YOU or YOUR family or friends would die from using that product. I would much rather an animal die then one of my family members or friends. Im sure if a dog was in the same position we are in, they would choose to test on us, but that is not the case. And again, humans arent the only ones who benefit from animal research. I think this post is long enough so I will stop there.... but if you didnt notice I am totally for animal research.

"Altered Goats"

Call to Action?

Proposal L

We can presume that a woman who volunteers for this study, in spite of the erroneous risks, would be able to handle the stress caused by the study. It seems unlikely that a perceived risk could create actual physiological risk. This appears to be equally as unfounded as the study itself. As I suggested to my group, it might be helpful to approach this study as a physician would. First and foremost, do no harm. As far as we know there are no inherent physiological risks associated with the study. My primary concern is the lack of informed consent. They are definitely not getting what they signed up for. If the perceived risk was real then consent would be a necessity.

Testing placebo hypotheses seems to be extremely difficult without informing the test subjects. I do think it could be worth studying, especially when the risks are virtually non-existent.

Research Proposal K

1) The researchers are targeting and exploiting individuals who are poor and lack the ability to use other prevention measures. If the ointment is shown to be effective, the question remains as how it will be made available to these individuals, since as noted they already cannot afford other measures.

2) Even though the ointment deters bites from Anopheles, the increase in bites by other mosquitoes poses a potential risk. Individuals using the ointment could be open to other diseases or infections carried by other mosquitoes.

3) At the end of the proposal it is noted that there is a slight risk of individuals developing long-lasting sores, and that these individuals would be studied in a sub-study. Also, that it is unknown if these sores are treatable. So what is to happen to the individuals who develop sores after the sub-study if the sores are not treatable?

If the researchers were able to address concerns and answer our questions (e.g. the ointment would offered to individuals in poverty for free), our verdict would still be to not allow the research to proceed. This is primarily due to similar reasoning that is stated in (1), the individuals to be used in the study would still be exploited.

Rachel, Kelsey, Kristian

Sunday, February 8

Research Proposal L

1. The factor of "risk" wasn't being controlled for. The experiment would need to include another control group that takes the placebos without being informed of the non-existent risk.

2. Something is wrong in principle about deceiving pregnant women and intentionally denying them treatment for morning sickness, if there is indeed a treatment.

3. We think the women should at least be told there is a possibility of receiving a placebo (even though all of them are). This is common practice in clinical trials, and as long as it's kept double-blind (i.e., neither the patient nor the clinician knows that the drugs are indeed placebos) we don't see how this would significantly alter the results.

4. In general, there are too many confounding factors-- not all of the women will experience the same degree of morning sickness, if at all, and their hormones are already fluctuating in response to the pregnancy. Furthermore, if the perceived risk does create a physiological effect, there's a possibility that the mother's and fetus' health may be affected. This risk may even outweigh the perceived "nonexistent" risk.

We realize that the women signing up for such a study would be committing themselves to more of a risk than they actually are being exposed to. However, we feel the fundamental problem is that the women are not providing fully informed consent because they do not know the full scope of the study. To do so may render the experiment impossible, but perhaps this it is reason enough not to see it through.

Saturday, February 7

Animal Research

First, it seems unethical--of course, tentatively using the term ‘ethical’-- to threaten the lives of members of one species (in this case, dogs) in order to potentially benefit the lives another species (humans).

Second is the issue of consent. Because dogs are not able to voluntarily consent to be subjected to discomfort, pain, and possibly death, in order to (potentially) benefit humans, they should not be used in the study.

Those who are pro-animal research generally base their feelings off of an assumption of human superiority. Because of this assumption, the cost to the ‘lesser’ creatures doesn’t outweigh the benefits to us. Generally it is thought that humans are superior because we have the ability to reason and use language. As I said in class, I don’t think this fact makes it more ethical for us to dispose of other living creatures as we see fit. Rather, I think it makes us more responsible to act in an ethical way and protect the lives of other ‘subordinate’ creatures that cannot speak out and defend themselves.

I’d like to respond to the point made in a previous post about how animals are “just animals” and if we kill an animal we can “just get a new one and problem solved”. In order to put this in perspective, imagine the following scenario: Scientists want to conduct the same study with the same ointment. But instead of using dogs, they choose babies in orphanages, because, well, humans can always give birth to more children (we are grossly overpopulated after all) and clearly they are “just” babies. Now imagine scientists claim “well, some babies might die from the study, but it will be a minimal number we assure you”. I find it hard to believe anyone would be willing to comply with the idea that this study would be ethical.

Let’s combine this example with the concept of some sort of innate human superiority. It is not as if these infants can reason, speak, or contribute to society in any real way. In fact, they are doing nothing but wasting tax dollars; they are, in effect, a drain on society as a whole. Given this, would those in favor of animal research be inclined to say that since they lack these skills, as animals do, they should be used to benefit those living creatures that can reason, speak, and contribute? I think not.

One final point, since my post it getting rather long. I am more than willing to admit that medical progress has been made using animals in research (i.e. insulin). I cannot say if I think the same progress would have been made without the use of animals, but that is not the current issue. The issue is whether or not benefit to a species that is able to reason, speak, and ‘make progress’ can take precedence over the cost to a species that cannot do so. As should be obvious by now, I am strongly inclined to say no.

Research Proposal K Response

The benefits that would have been achieved from the study did not outweigh the risk because:

1) medicine/ointment proposed for the study was meant for prevention but there are presently much more effective and cost-efficient ways of preventing malaria.

2) the increased risk from non-Anopheles mosquito was proclaimed to increase due to the application of the ointment hence increasing the risk for several other mosquito carrying diseases just for determining the effectiveness of an ointment.

Question we would like to ask:

Do they have another way of human testing ? (like in a lab with controlled environment for managing and treating the side effects or complications that might arise)

Are they going to provide sufficient information to the volunteer and will they be providing medical facilities (from basic to specialized treatment) in case of complication ?

If they could answer the question of an alternative way of human testing, particularly in a laboratory where people are not exploited, complications can be managed efficiently and effectiveness of the ointment can be diligently monitored then we (committee) could reconsider the proposal. However before agreeing to the proposal we would also like to see that all forms of treatment and medical care are available for the volunteers.

Lauren, Lungsi, and Thando

Proposal J and animal research in general

Reaction to research proposals

Proposal J brings up the issue of animal research and whether it is ethical to use animals to test the ointment discussed in the article. In principle, I believe that the use of animal testing is wrong. The reason for this is that animals are not capable of giving voluntary consent and therefore should not be used in this testing.

Research Proposal K:

Proposal K discusses using volunteer human subjects in impoverished areas to test the ointment for malaria. The ethical issue here involves targeting a poor area to do the study on. This seems to be somewhat minor to me, since the subjects are volunteers in the study.

Research Proposal L:

Proposal L discusses the placebo effect and the neurochemistry behind this phenomenon. The study uses the volunteer pregnant woman. The ethical issue here is that the study does not allow for full disclosure to the volunteers involved in the study, because of the nature of the study. I feel that although it is deceptive to the volunteers, it is necessary in order to find out more behind the placebo effect.

Recent octuplet story

Interesting story about a single mother of 6, now 14 using in-vitro fertilization to have more children. Asks many ethical issues regarding both the doctors involved in the procedure as well as the mother. As far as from the doctors perspective, is it ethical for the doctors involved to go through with the procedure and implant the harvested eggs? Do the fertility doctors involved have the right to deny her access to these eggs?

As far as the mother, there are several ethical issues at hand. For one, being a single mother, is it ethical for the mother to have several more children? Are these children being cared for properly and not merely an obsession for the mother? Also, the story also brings up issues of why she is having these children. Is there a financial incentive that is involved that is enticing the mother to continue to have children?

Personally, I believe that it is very selfish of the mother to continue this behavior. I feel that it is impossible for a single mother to care for and develop relationships with these children. It seems to me that no single person is capable of providing the care and affection to 14 children. As far as the doctors are concerned, it is a difficult question to answer. I feel that it is wrong for the doctors to allow this to happen, but it is a very difficult issue to deal with. I would like to hear what all of you feel about this issue.

Friday, February 6

Clarification about Case Study Discussion

Thursday, February 5

ScienceBlogs...check it out!

Wednesday, February 4

Risk/Benefit Vs. Principle

Asking the question "Is this science really worth pursueing?"

So how far do we take science?

A question like this we faced in the 1940's the pursuit of nuclear fission--one result was a potentially awesome power source (though, in my opinion, our government is too stupid to realize it) and another was the atomic bomb.

Another, more recent, example is Hadron. Do we really need to know what makes up subatomic particles if we already know how to work with molecules (chemistry!)?

So now that I presented two examples, where do we draw the line? Can a definite line really be drawn here? I can see this becoming more and more of an issue as our understanding of science grows. Perfect example of a question we now face (or we are going to face.. pretty sure we're facing it now though) is genetic engineering in humans. There are a lot of issues in this topic--like curing genetic disorders, etc etc. But whose to say we stop at genetic disorders? If we can get rid of some cancers, why not get rid of "ugliness" or choose the eye color of kids?

My personal opinion is that science is something we should pursue but theres limits. Like genetic engineering in humans isn't really something we should pursue to the point where we can manipulate genes. Its cruel, but I think genetic risk is a risk we should take. Removing it makes reproducing more of a chore than something special. Instead, we should pursue cures to diseases, injuries and the like. Take for example the (near) science-fiction idea of growing organs. That'd be totally awesome... "Kidneys blew up? Here! Have a new pair, made from your own DNA!"

So how does everyone else feel about this idea? I really didn't touch on "how" as I think there is absolutely no clear-cut answer to this question.

The Results of the Tuskgee Study

(Also, if anyone can find anything about how the study helped the scientific community better understand syphilis please share it.)

Source: http://www.tuskegee.edu/Global/Story.asp?s=1207598

Involuntary Hospitalization - Part 1

Two movies that come to mind related to involuntary hospitalization are the Jack Nicholson "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest" and the other is "Europa'51" starring Ingrid Bergman. For copyright reasons I can't post the article but I will try to provide a zest of the article ("Once the Wheel Are in Motion: Involuntary Hospitalization and Forced Medication" Burton Seitler; Ethical Human Psychology and Psychiatry, Vol.10, No.1, 2008). In the article he mentions two of his patients. Please bear with me as this blog will run long because of the two stories involved but the stories are an interesting.

Background

Terminologies:-

Insanity- This term is a legal invention because there's no such thing as "insanity" in psychology.

Involuntary Hospitalization (Civil Commitment)- Term for the legal procedure to compel an individual (against his/her will) to receive treatment for presumed emotional problem. (Conditions:- too dangerous to themselves or others; from the presumed problem suffer diminished capacity and lack insight to their problem).

IH = involuntary hospitalization IU = intervention unit PTSD = Post traumatic stress disorder

The author mentions that either one of the conditions was sufficient for IH in at least 34 states and in 1998 no less than 51 bills were introduced in 7 states relating to IH. Though most states require "proof of dangerousness" the term dangerousness is a highly ambiguous term (even among clinicians). American Psychiatric Association (APA) in 1993 (from studies done) stated- "......psychiatrists have no special knowledge or ability with which to predict dangerous behavior........even with patients in which there is a history of violent acts, predictions of future violence will be wrong in two out of every three patients".

The Two Cases - Hospitalization

Case1 (Nancy, not real name):-

25yr old, petite (5'1"), employed was seeing the author (Dr.Seitler) for her difficulties with her parents (particularly mother). She was having conflictual feelings regarding leaving home, finding & keeping a boyfriend and fundamental issues involving trust. She went for therapy whenever, she experienced personal anguish or felt depressed and besieged by obsessional thoughts. She was seeing Dr.Seitler for 2yrs during which she was feeling better, she changed her job to a happier position and took up part-time after hours work in her chosen profession. She saved enough money to leave her parents home and find an apartment in a nice neighborhood. She felt she achieved her goals from the therapy and decided to go it alone.

After about 1yr, Dr.Seitler received persistent demanding phone calls from Nancy's mother irately ordering him to commit Nancy because she failed asking the mental health IU. After about 6weeks the local emergency IU (different person in charge) agreed to the mother's demand to commit Nancy and Dr.Seitler received a call from the psychiatric hospital and mentioned that Nancy wanted to speak with him. She requested Dr.Seiteler to visit her.

Dr.Seitler's conversations with the psychiatrist at the hospital informed that Nancy objected hospitalization and they administered antipsychotic injections as a standard protocol. He was also told that Nancy was doing fine and was getting along well with other patients and completely abided the rules and routines. However, they were annoyed that she wore black outfits exclusively even when told not to do so Was it that Nancy was wearing the same clothes and hence soiled and smelled?). On Dr.Seitler's visit he noticed that Nancy was exceptionally clean diligently washing her own clothes. The psychiatrist hinted Dr.Seitler that if Nancy wore a different outfit they could hasten her release.

Dr.Seitler addressed the "black dress" issue to Nancy and asked her how she got here. She recounted that, the local IU along with her parents and 2 policemen came to her workplace asking her to accompany the policemen to the hospital. She agreed thinking it was unreal. But just as she left the workplace and was about to get inside the police car she realized and she got second thoughts. When she began to panicked she was knocked to the pavement, handcuffed and put into the car. She told she was treated so rough she still had marks, bruise and abrasions shown to Dr.Seitler (note she is a petite, 5'1" woman).

After Nancy stopped wearing black clothes, in short order she was released.

Case2 (Ed, not real name):-

40+ yr old man, was suspicious of his wife that she was putting illegally controlled substance in his coffee for over 2 weeks for which she denied. However Ed went to the lab and found traces of the substance in his coffee. Soon after this he filed a restraining order against her and moved out of the house. She immediately countered him with her own. 2 months passed during which they neither saw nor spoke to each other but she left numerous voice mail messages for him at his new living place insisting him to come home with verbal threats of destroying him. Then she filed a

complaint to the local IU stating Ed posed imminent danger to her.

The local IU paid a visit to Ed's new living place asking him to accompany them and when Ed asked if he had any choice they replied no. Ed remained calm and composed (unlike Nancy who demonstrated objections) and was granted the opportunity to make a call upon request. He contacted his attorney.

The author mentions that Ed was now in a mechanized bureaucratic hospitalization process, mechanized because questions such as Ed's wife wanting him to get

hospitalized as an ulterior motive was never raised. Ed was then committed to the psychiatry ward of the county hospital.

Ed's attorney negotiated with the hospital administration on grounds that he would receive psychotherapy. Ed's stay in the hospital was about 5days. His attorney contacted Dr.Seitler for seeing Ed upon release.

The Two Cases - Aftermath

Case1 (Nancy):-

Nancy was receiving antipsychotics in the hospital and was not advisable to stop immediately because of withdrawal effect. After her release the hospital neither gave any medication nor any prescription. When the psychiatrist was informed of this they replied that since she was discharged she no longer fell under her jurisdiction.

At her job, Nancy needed a psychiatric evaluation to return to her job. Dr.Seitler referred her to one of his colleagues for evaluation who reported "she is not mentally ill, is not a danger to herself or anyone else, and can return to work immediately". The employer did not except the report and kept her on payroll till they got a report from psychiatrist of their own choosing. Though the report was still same, it took her 3 months to resume her previous duties at work.

Nancy became distrustful of the system, felt let down, dehumanized and traumatized. The author calls her experience as iatrogenic PTSD. She generalized the failure to everyone including the author himself. Consequently, she began to cancel her appointments with him.

Case2 (Ed):-

It was never established that Ed was previous, currently or even potentially dangerous and the hospital thought Ed was safe enough to be discharged in relatively short period of time. Ed had also expressed his wishes not to receive any medication. However, the hospital continued to medicate him.

Ed felt disgraced and humiliated, and was unable to return to work for nearly 2yr for fear of perception by people around him.